Many places don’t track it. The ones that do, don’t count it completely. In fact, there’s only one that records the race and ethnicity of every person infected by coronavirus, according to one database.

Douglas County, Nebraska.

And while that might seem like a shining badge for officials in the Douglas County Health Department, gathering detailed information to inform strategies is all health officials can do in lieu of a known treatment or vaccine.

“This is our primary weapon against Covid-19,” said Dr. Anne O’Keefe, senior epidemiologist with the health department.

That’s helped in disseminating information, but community health leaders say it’s only a small step toward the solution they and officials across the country have demanded from the start.

“We don’t have adequate testing,” said Andrea Skolkin, CEO of OneWorld Community Health Centers . “Now I’d say we’re sufficient but we’re not doing mass testing which is what we think is needed in the community.”

As the nation has started to comprehend where the pandemic strikes hardest, data shows people of color contract and die from coronavirus at rates multitudes higher than white people.

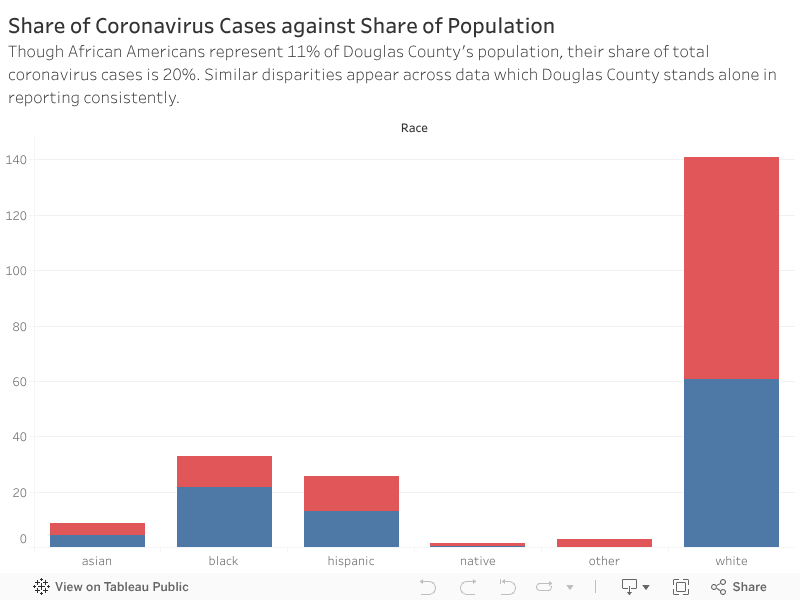

In Douglas County, African Americans represent 21% of cases but only 11% of the population. Likewise the zip code with the highest cases is in predominantly Hispanic South Omaha. In contrast, white people make up 60% of cases but 80% of the population.

But Douglas County might be the only place you can say those numbers definitively. According to a list compiled by the Solutions Journalism Network, many counties and states listed a quarter of its cases race category as “unknown.”

The problem was so commonplace that when Matthew Kauffman, the Connecticut-based journalist who built the database, ran the numbers on Douglas County, he had to double then triple check the perfect record. But that should be the standard not the outlier as governments try to understand who’s at risk, where to direct resources and whether efforts are making a difference, he said.

“If you’re going to solve a problem,” Kauffman said, “you have to understand the problem.”

That’s been the goal of the Douglas County Health Department.

As soon as a case is confirmed, one member of a team of health department interviewers calls that person. To keep up with demand, the department increased that team from three to nine people and trained additional staff members to make the same calls if case loads got too high.

Once they’re on the phone, interviewers gather details about who the person is, where they’ve been recently and what steps to take next. With that information the county builds contact tracing maps and strategizes where to focus efforts to continue stamping out the virus’ spread, O’Keefe said.

Part of that strategy has been to aid the hardest-hit communities. In Douglas County that means North and South Omaha where officials have reached out to community organizations, translated public information and provided more testing to facilities like the Charles Drew Health Center and OneWorld Community Health Centers.

Having data to back that up is invaluable O’Keefe said. If they missed recording these kinds of details for only a fraction of their cases, it would start to sew uncertainty.

“It could be that if you have a lot of missing information than maybe no one would even know there’s a discrepancy,” she said. “People would just assume everyone has the same risk.”

Skolkin said that aid has been helpful, however it still pales in comparison to what the community needs.

“We received 100 tests for asymptomatic patients,” she said. “I don’t call that necessarily a significant, huge amount of tests.”

But even that small increase nearly quadrupled their testing capacity. Last week, the community health center only did 35 tests. The week before they did 10. Skolkin said she now considers that number sufficient, but it’s far from the mass testing they need. And she’s not alone in that as health care and government officials continue to lambast the nation’s inadequate testing capacity.

Especially in a community where social distancing and isolation is near impossible. Like so many other low-income, minority groups nationwide, many in South and North Omaha don’t have the luxury of choice many others do.

“That’s why they’re not getting tested,” said Skolkin, “because they’re going to work.”

They’re the essential workers that keep products moving through supply chains, the people who keep facilities like hospitals running. They can’t choose a car over a bus. They might live in multigenerational homes where they can’t keep six feet of space between people.

Kauffman said that’s at the heart of why tracking the race of coronavirus patients and victims matters. As the pandemic reveals racial disparities nationwide, he said county health departments have a responsibility to tell the full story.

“Certainly if this is a reflection of the impact on people in frontline jobs, putting their lives on the line every day for the rest of us, keeping the busses running, the mail delivered and working in hospitals,” Kauffman said, “don’t we owe them a strong standard of care?

Skolkin wants to see the same thing. While Douglas County’s reporting already indicates the pandemic’s racial inequity, the real problem is what the numbers don’t show. Tens of thousands of people uncertain of what the impact the virus’ has wrecked on their community, many going untested and working every day without a viable alternative.

The hardest part as a community health provider is not being able to offer that, Skolkin said. As the hospital network closes down for at least three weeks, turning to telehealth and other remote services, health care workers in South Omaha are doing everything they can to maintain the health of the community.

They just wish they had the tools they need.

“We just want everyone to feel like they have a place to go,” she said.